No red line

One thing we sometimes forget is that people - populations - look at events in the light of their own history, their own culture, which can sometimes be significantly different. This obviously applies to everything, and therefore war is no exception. If we then consider that war is truly a decidedly explosive set of events, both factually and figuratively, and therefore extremely changeable, subject to constant dynamics and, in a certain way, endowed with a life of its own, it is easy to understand how a different cultural perspective is inevitably reflected not only in the perception of war, but also in its conduct.

The Western art of war, for example, is profoundly marked by the idea of attack - also because practically all Western wars have been, historically, wars of expansion.

From the Western point of view, therefore, war is predominantly an offensive fact. Europe, in the course of its history, has essentially seen three major invasions, none of which has ever conquered it entirely: the Mongol, the Islamic and the Ottoman. Conversely, it has brought war to every corner of the world, even the most remote.

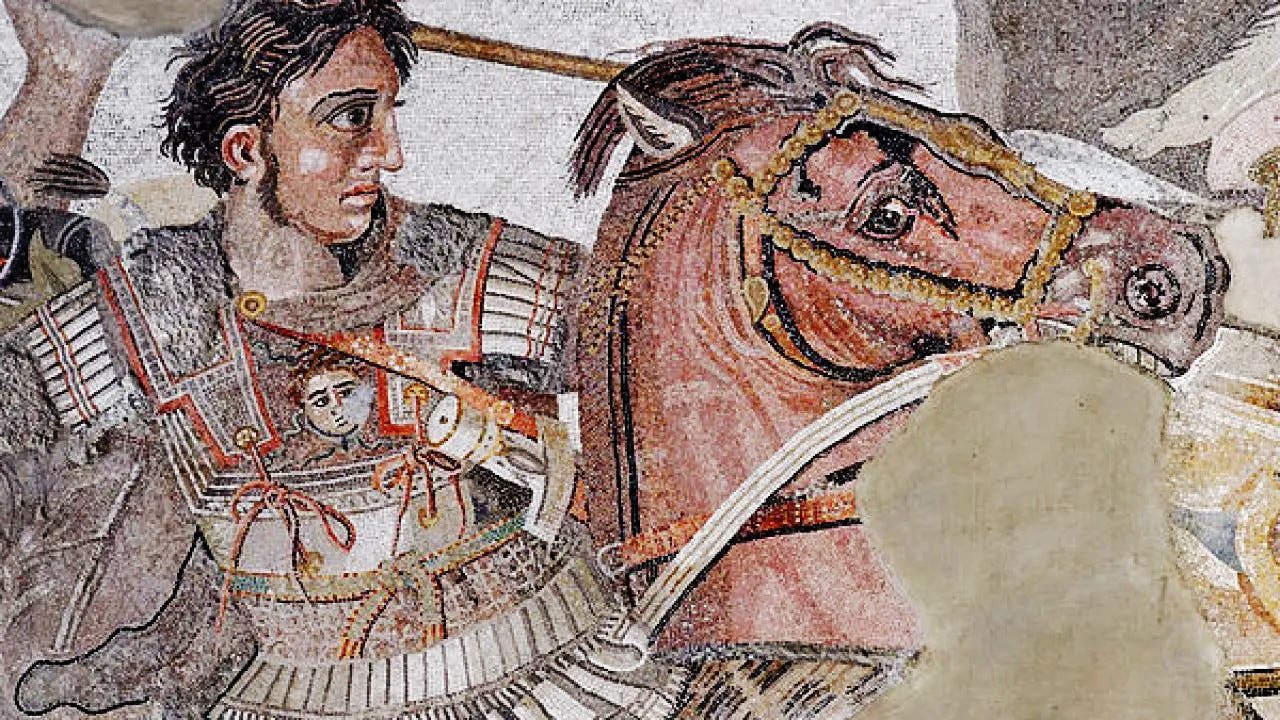

This vision of war action is so rooted in our culture that it is difficult for us to conceive the act of war differently. And, regardless of the course of the conflict, it is conceived around the idea of decisive action. From the Macedonian phalanx to the nuclear first strike, this is the common thread of Western military thought.

Since the emergence of the hegemonic power of the United States - which has made attack the foundation of all its military doctrine - the offensive concept of war has strengthened, informing the entire military-industrial complex, and in turn reflecting on Western culture, on its common sense.

Without wanting to recap here things that have already been said several times, one could in a certain sense say that the offensive cultural approach has ended up prevailing to such an extent that, at times - and in an increasingly evident way - war has not only assumed the role of the main instrument (not an instrument, but the instrument), but has ended up overlapping with the ends: war no longer as an instrument to achieve objectives, but as an objective in itself.

Here the paradox of a millenary impulse aimed at achieving the maximum capacity of decisive action, which is then reified in action for action's sake, is realized; the Clausewitzian principle (never reiterated enough) of war as an instrument to otherwise achieve a political result, is transformed into a state of permanent war, which no longer seeks either the decisive act, or the achievement of a political objective that is placed beyond war.

This has largely depended on the fact that - precisely - war has also become (if not predominantly) aimed at achieving economic objectives, beyond and more than political ones. It is, in fact, the apotheosis of the capitalist idea, precisely because there is no other production-consumption chain as extensive and fast. The voracity of war, in terms of consumption, is unparalleled.

This is even more evident if we observe the Western wars of the contemporary era, in which not only does the utilitarian calculation clearly prevail, the cost/benefit evaluation, but it goes to the limits of wars without a purpose (at least a clear one), from which one withdraws as from a poker table, when one simply no longer feels like playing. Wars that have lasted decades (and cost hundreds of thousands of victims), and justified by the achievement of an objective, which are suddenly put to an end, without having achieved the declared purpose, and without having suffered a defeat on the field. Think of Vietnam or Afghanistan.

The paradox remains in existence, however, it is not resolved. The Western cultural setting is still aimed at the idea of war as an offensive action, and this is still the inspiration for military doctrines and, consequently, the articulation of the armed forces. But, at the same time, the focus has shifted from the decisive factor to consumption. The duration of the war is no longer (simply) the time necessary to achieve political objectives, but the time adequate to the needs of the production-consumption-production cycle.

The Russian-Ukrainian conflict, which has been going on for thirty months now, is a privileged observatory from infinite points of view, because here not only different weapon systems and different military doctrines are confronted, but also even more different historical and cultural conceptions of war. Which, obviously, is significantly reflected not only in the perception of war, but also in its conduct. And it is not just a question of the fact that for Russia this war is existential (the existence and integrity of the Russian nation are threatened), while for the collective West it is only part of a global strategy for the defense of its hegemony.

The radical difference in perspective is such that it makes it difficult to understand - regardless of how one positions oneself - the Russian point of view.

First of all, it must be reiterated that the launch of the Special Military Operation, in February 2022, even if in tactical terms it was offensive, for the Russians, in strategic terms, it was a defensive move. Moscow clearly perceived the aggressive rise of NATO, which if the roles were reversed would probably have attacked already in 2014.

Another factor that tends to be forgotten is also self-awareness.

Russia knows that it is a nation very rich in resources, and therefore highly attractive to a West that, on the contrary, has relatively few, and has always resorted to plundering those of others. But it is also aware of its own weaknesses - which even the most die-hard fans in West often tend to forget. It is a huge country (the largest in the world), with a surface area of about 18 million square kilometers (the whole of Europe has about 10 million), but with a population of 146 million (Europe has 745 million).

This alone helps us understand two very simple things, but not always as obvious as they should be: there is a huge territory to guard (20,000 kilometers of land borders!), with a very limited human potential to draw on, which makes it doubly complicated to protect it, and there is the need to preserve the human resource as much as possible, even more precious than for other nations precisely because it is (relatively) scarce [1].

Furthermore, although Russia is considerably more powerful than Ukraine, the latter is in fact only a sort of enormous Private Military Company of NATO, and therefore the comparison should not be made between Moscow and Kiev, but between the Russian Federation and the 36 countries of the Atlantic Alliance (plus another ten allies of the USA).

We are therefore in the presence of an absolutely symmetrical conflict. And this alone is sufficient to explain both the duration of the conflict and the fact that this is not a unilateral succession of successes by one side; on the contrary, it is completely normal for both sides to score hits. Indeed, considering the symmetry of the conflict, it is noteworthy that Russian successes are so much greater than Ukrainian ones, both in quantity and quality.

From this perspective, the recent NATO-Ukrainian incursion into the Kursk region is in fact nothing extraordinary - although of course, and for similar but opposite reasons, both sides have an interest in emphasizing it a lot.

Let's just say that it was easily predictable. Already shortly after the start of the Special Military Operation, in the aftermath of the withdrawal of Russian troops from the Kiev and Sumy regions, I myself wrote that "in the north-east of the country, there is a border line several hundred kilometers long, which after the withdrawal of Russian troops is again in Ukrainian hands. And that, consequently, offers the possibility of attacks on Russian territory” [2]. Obviously, the Russian General Staff also considered this eventuality, and evidently considered it more economical to maintain a loose defense on that stretch of border, believing in any case to be able to intervene at a later time, rather than fortify it and/or commit more prepared troops and in greater quantities.

Moreover, as they know well in Moscow, inviting the enemy to attack means putting him in a condition in which he will face more significant losses - which is one of the main Russian objectives.

Even if, obviously, Kiev speaks of 1,000 square kilometers of conquered Russian territory, the reality is very different. Intent, because the penetration is mainly due to DRG units [3] each composed of a few dozen men, who have pushed deep for about twenty kilometers, along a front of about fifty; and then because within this area there is no solid and widespread presence of Ukrainian forces. What has actually happened is the creation of a large pocket in Russian territory, about twenty kilometers deep, which, after the stabilization of the front, risks becoming a trap for Ukrainian forces. In any case, it must be reiterated that the Ukrainian action is not extraordinary, but rather the fact that it did not happen before. And, not secondarily, that Russia has an infinitely superior strategic depth, theoretically even 10,000 kilometers.

Historically, in modern and contemporary times, Western armies have reached Moscow twice, only to emerge defeated.

The same issue applies to the so-called red lines. Just think about it for a moment, avoiding media conditioning, to realize I realize that this is a real nonsense: in war, there are simply no red lines. Even more so in a war of this scale. It is largely a propaganda minuet between the parties, no more and no less than the succession of supplies of new weapons systems to Kiev.

In both cases - a new red line crossed, a new weapons system supplied - neither the strategic nor the tactical framework changes, it is pure and simple fog of war, functional to the concealment of the different points of view on the conflict: for NATO, it is a question of achieving certain objectives (a clear detachment of Europe from Russia, the economic subornation of the latter to US interests, the start of a large-scale war production cycle, the attrition and destabilization of the Russian Federation...), while for Russia it is a question of defending its living space. Neither of the two wants to reach a direct confrontation now.

If NATO had wanted it, it would have had endless windows of opportunity to go on the offensive, even if it felt a pressing need to justify it in the eyes of its own public opinion. If Russia had wanted it, the same would be true.

The point is that both are aware that, in long-term strategic terms, the conflict is inevitable, but neither is ready to support it at this time, under these conditions.

What no one knows for sure is whether this war will last long enough to then turn into the real Russia vs. USA-NATO war, or whether it will instead run out of steam before the time for the real conflict is ripe.

At the moment, it seems that the United States is preparing, once again, to leave the table. After Saigon and Kabul, the time of the "bye bye, Kiev", is approaching.

Notes

1 - From this perspective, the Ukrainian conflict is actually profitable for Moscow. Even though the losses are quite significant (probably around 100,000 men, even if compared to at least 600,000 Ukrainians), it must be kept in mind that, between the population of the annexed areas and refugees from all over Ukraine, it has acquired about ten million new inhabitants. And, obviously, in addition to this there is the acquisition of particularly rich territories (in terms of minerals and not only), the expansion of control over the Black Sea, and the increase in its strategic depth, further distanced from the main cities.

2 - Cfr. “La Guerra Civile Globale”, Enrico Tomaselli (self-publishing, available on Amazon).

3 - (Diversionno-razvedyvatel'naâ gruppa, DRG), mobile reconnaissance and sabotage groups.